Invasive Species Lecture Notes

I am teaching conservation biology at Silliman University in Dumaguete, Philippines. These are some lecture notes for this class. As with my lectures notes for my coral reef class, and my fish bio class, this is not meant to be an online textbook, but a pointer to a lot of good resources, plus my comments and thoughts to put these resources in context.

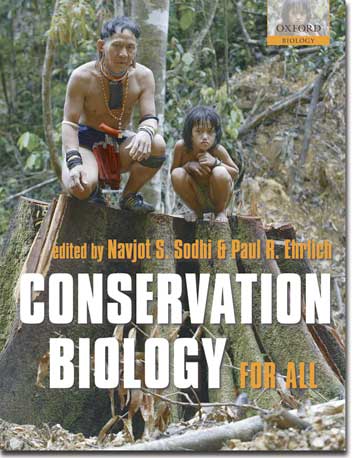

Excellent Textbook

I am using this excellent free textbook by Sodhi and Ehrlich, which you can download at the link below (click on the book cover image).

This book I am using as the main framework for the class.

For a number of topics, I am supplementing this textbook with papers from the scientific literature and other material. The two topics in conservation biology which interest me particularly are invasive species, and ecosystem stability.

Invasive Species

Invasive species cause considerable damage in many ecosystems world-wide. Species brought in by humans into new ecosystems, either directly or indirectly, have the potential to massively mix up the balance of the ecosystems in which they arrive.

The impressions I get from reading the literature are:

- Some invasive species are worse than others in their impact. A popular ranking divides them into 4 levels of impact (Molnar, J. L., Gamboa, R. L., Revenga, C., & Spalding, M. D. (2008). Assessing the global threat of invasive species to marine biodiversity. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 6(9), 485-492.).

- Small to mid-sized generalists witch high reproductive rates are often successful as invasive species. Being venomous helps.

- Large, complex, continental ecosystems are often the sources of invasive species, smaller, island ecosystems are often the targets.

- Ecosystems which are already considerably stressed are more susceptible to become the hosts of invasive species.

- Eradication programs can work, but are hard work and might need considerable efforts like the introduction of viruses.

Below are three blog posts which I wrote about the topics, plus a video I made about the invasive lionfish. The blog posts avoid scientific jargon but aim to be mini-reviews of invasive species on islands in general, of the invasive “mosquito fish” which is invasive in the Philippines, and the lionfish which is invasive in the Caribbean. The video includes a brief lecture of mine on the lionfish invasion.

This paper contains a rather complete list of the invasive freshwater fishes in the Philippines. I disagree with it in its too rosy assessment of the “beneficial” effects of introduced effects, but it’s a good piece of scholarly work nevertheless:

A Tragedy on Multiple Levels: The Nile Perch

The great African Rift Lakes are amazing places for a fish biologist because of the adaptive radiation which the Cichlids in these lakes underwent. A few Cichlid species from connected rivers blossomed into

Then, sometime in the mid 20th century, well-meaning agricultural agencies introduced the Nile perch into Lake Victoria. This large, fast-reproducing, unselective fish-predator very quickly spread throughout the lake and drove many of the small Cichlid species to the edge of extinction. A very complex food web was replaced with a much simpler one, with phytoplankton, zooplankton, small shrimp, shrimp-eating fish, and the Nile perch on top. Large Nile perch started feeding on small Nile perch.

The decrease in water quality in Lake Victoria and the general degradation of environmental conditions likely contributed to the decline of the Cichlid fauna and the take-over of the Nile perch. Some Cichlid species are recovering, The recovery is very specific to only some ecological niches.

The massive Nile perches can’t be sun-dried like the Cichlids were previously, and is often processed in industrial facilities, for export. Hence, the introduction also had significant economic effects on the region.

Pringle, R. M. (2005). The origins of the Nile perch in Lake Victoria. BioScience, 55(9), 780-787.

Goldschmidt, T., Witte, F., & Wanink, J. (1993). Cascading effects of the introduced Nile perch on the detritivorous/phytoplanktivorous species in the sublittoral areas of Lake Victoria. Conservation biology, 7(3), 686-700.

Downing, A. S., Van Nes, E. H., Janse, J. H., Witte, F., Cornelissen, I. J., Scheffer, M., & Mooij, W. M. (2012). Collapse and reorganization of a food web of Mwanza Gulf, Lake Victoria. Ecological applications, 22(1), 229-239.

Natugonza, V., Ogutu-Ohwayo, R., Musinguzi, L., Kashindye, B., Jónsson, S., & Valtysson, H. T. (2016). Exploring the structural and functional properties of the Lake Victoria food web, and the role of fisheries, using a mass balance model. Ecological Modelling, 342, 161-174.

Marshall, B. E. (2018). Guilty as charged: Nile perch was the cause of the haplochromine decline in Lake Victoria. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 75(9), 1542-1559.

Invasive Species In Australia

Australia is a curious place, and its unique fauna made it a prime target for species invasions.

To begin with, the Australian continent separated from the rest of the landmasses of the planet before the first “true” (eutherian) mammals evolved. Hence, with the exception of a few rodents which came on floats from Indonesia, the mammalian fauna of Australia was restricted to marsupials and monotremes. These more basal mammals usually don’t compete well with “modern” mammals. One reason might be that they generally have a smaller brain weight/body weight ratio, and lack some brain structures which eutherian mammals have, such as the corpus callosum linking both brain hemispheres.

Look at this nice animation of continental drifts during the last 450 million years:

Then, as in most places outside of Africa where large mammals co-evolved with us, stone-age humans eliminated the megafauna of the continent once they go there about 44 000 years ago. This is not a moral judgement of these early hunters (“Cancel the stone age hunters or else!”), but simply an observation, that humans with their intelligence, team work and tool use are too powerful an ecological force for most large mammals unacquainted with humans.

Roberts, R. G., Flannery, T. F., Ayliffe, L. K., Yoshida, H., Olley, J. M., Prideaux, G. J., Laslett, G. M., Baynes, A., Smith, M. A., Jones, R., & Smith, B. L. (2001). New ages for the last Australian megafauna: Continent-wide extinction about 46,000 years ago. Science, 292(5523), 1888–1892.

So, when the British colonialists started bringing over eutherian mammals they found a continent which had started out with a somewhat reduced mammalian fauna, which was then further reduced by stone age hunters. A paradise for the introduced rabbits, cats, camels and others. All kinds of resources, little competition and predation! Few places (small oceanic islands) have been hit as hard by invasive species as has been Australia.

The Australian government has set up a very informative webpage covering the main invasive species into the continent: rabbits, foxes, cats, cane toads (also covered in the introductory blog post linked above) and camels.

The cane toad has become a part of the culture of the Australian state of Queensland, with toad races happening in pubs. The density of these toads is great – another example of an invasive species which reproduces to much greater numbers in its invasive range than its home range. The animal is very toxic to birds, and also to humans, with psychedelic effects in humans. Again, we have the ideal invasive profile: small, fast reproducing, protected from predators (by poison in this case), and a food generalist.

Phillips, B. L., Brown, G. P., Greenlees, M., Webb, J. K., & Shine, R. (2007). Rapid expansion of the cane toad (Bufo marinus) invasion front in tropical Australia. Austral Ecology, 32(2), 169-176.

Strive, T., & Cox, T. E. (2019). Lethal biological control of rabbits – the most powerful tools for landscape-scale mitigation of rabbit impacts in Australia. Australian Zoologist, 40(1), 118–128.

Hart, Q., & Edwards, G. (2016). Outcomes of the Australian Feral Camel Management Project and the future of feral camel management in Australia. Rangeland Journal, 38(2), 201–206.

Tow Very Curious Examples

Some invasive species come to their invaded new homes by accidents; some by misguided agricultural policies; but the invasive species in the next two examples got there because very rich guys wanted to have safari parks.

The Calauit Safari Park in the Palawan province of the Philippines was established by Ferdinand Marcos in 1976. A number of African savannah animals were brought to the Philippines, interestingly only the population of the reticulated giraffe (Giraffa reticulata) and Grévy’s zebra (Equus grevyi) persisted, several smaller antelope species didn’t make it.

So far the zebras and giraffes have not spread

It’s worth noting that the tribal people who inhabited this part of Palawan were forcefully resettled, hence we have again an example of how environmental problems go hand in hand with social injustices.

This is in the Philippines (!):

Another example of such a species invasion by rich dude are the hippos in Columbia, brought there by the late drug lord Pablo Escobar. A small population of these large African mammals escaped from Escobar’s ranch after his death, and multiplied to more than 100 animals by now. The animals are ecosystem engineers, and change the shape of the waterways they live in; they consume so much plant material that they influence the energy balance of the ecosystem significantly in this way. Projections of hippo numbers speak of more than a thousand animals within just a few more decades.

Efforts are now being made to chemically sterilize them to keep their numbers low; And the hippos have even been subject of a silly US lawsuit by now.

Recreating the Pleistocene?

The Caluit safari park’s giraffes and zebras, and the “Cocaine hippos” in Colombia are also unusual invasive species because they are megafauna – large animals (>> 100 kgs) which have significant effects on the ecosystems and landscapes in which they live.

“Pleistocene rewilding” is the idea to not just save species from extinction and ecosystems from degradation, but to restore the trophic webs of the early (pre-human extinction) Pleistocene, with large herbivores on the apex. A daring idea. Does it make sense? Here is one con and one pro paper; I tend to agree with the con point of view, but nevertheless, this is an intriguing grand idea.

Rubenstein, D. R., & Rubenstein, D. I. (2016). From pleistocene to trophic rewilding: A Wolf in sheep’s clothing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(1), E1.

Donlan, C. J., Berger, J., Bock, C. E., Bock, J. H., Burney, D. A., Estes, J. A., Foreman, D., Martin, P. S., Roemer, G. W., Smith, F. A., Soulé, M. E., & Greene, H. W. (2006). Pleistocene rewilding: An optimistic agenda for twenty-first century conservation. American Naturalist, 168(5), 660–681.

Ecosystem Stability

Is a more complex ecosystem more stable? How does this complexity contribute to stability, if so? Why are species extinctions a bad thing, not just on their own, but in relation to ecosystem stability? This is a question which is more complex than it seems at first. A randomly assembled simulated (theoretical) ecosystem will be less stable when more complex … surveys of actual, real ecosystems show the opposite effect, more stability with more complexity. The discrepancy is called “May’s paradox”. The solution lies in the fact that real ecosystems’ connections between species (such as species A preying on species B) are not random, but generally weak, and lack strong, long-range relationships. These relationships don’t form randmly but step-by step during the build-up of an ecosystem.

Understanding these fundamental principles will help anyone concerned with the trajectories of ecosystems when they lose species, in my opinion. Also, invasive species often lead to a collapse of ecosystem stability – how does this work? The comprehension of ecosystem stability and the field of invasive species are tightly linked, in my opinion.

This paper gives a good overview over the topic:

Wilmers, C. C. (2007). Understanding ecosystem robustness. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(10), 504-506.

This is a nice paper which works out how the stable connections of an ecosystem are built step-by-step, using soil organisms as an example: