Thoughts on the Convict Fish

I had previously written about the convict fish, or engineer blenny, or engineer goby, which is in fact neither a goby nor a blenny. The scientific name is Pholidichthys leucotaenia, and it belongs in its own family, the Pholidichthyidae, with only 2 closely related species.

The curious behavior of this fish is that the juveniles, which school and feed on plankton, live in burrows with one large adult, which looks a bit like a blunt-nosed moray eel. The juveniles spend the night in the burrow, sticking to the walls, and it seems they are feeding the adult. There is division of labor between the adult (burrow construction) and the juveniles (forraging). In the seminal paper on this fish, (Clark et al., 2006), the authors state that Clusters of larvae or juveniles hung from the burrow ceiling by mucus secreted from glands on their heads and often were scooped into mouths of adults and then released apparently unharmed.

Last weekend my dive buddy Matt found us a young adult convict fish on the sandy slopes of Dauin, the Philippines’ “Muck Diving” hotspot. This fish was seemingly at a transition stage and had just become an adult. It was ~ 20 cm long, ventured around on its own, and it was moving about on the sand and in the rubble in eel-like fashion, and not swimming mid-water like the juveniles do. It almost seemed as if it was looking for an appropriate spot to build a burrow. Or was it searching for a mate? Here is the video:

The 2013 paper of mine which I am talking about in the video is called Why are there no eusocial fishes?. In the paper I argue that eusociality, the social division of labor where only some individuals reproduce, like in ants or bees, is absent in fishes due to several features of aquatic environments. These features are include the wide distribution of fish larvae in the ocean, which makes it unlikely that close relatives end up next to each other as adults, and start cooperating – this kind of cooperation of adults is thought to be one of the evolutionary starting points of eusociality.

When I wrote that paper, about a decade ago in Sydney, I did not know about the convict fish’s biology yet, even though I had seen it on my dives in the Philippines. The convict fish, with its division of labor between juveniles and reproductive adults (like in eusocial insects, such as bees or ants) might not quite be truly eusocial, but it certainly represents a somewhat related social system, or possibly a species on its way to eusociality. Do all the convict fish juveniles have the potential to become full-blown, breeding adults? Or are there true “workers”, as in eusocial insects, which will never reproduce, but only forage for the benefit of the colony? This is a key question, in my opinion. I know of no evidence so far that some of the juvenile convict fish are “only” workers, looking at the fish’s chromosomes might be a good start. Chromosome arrangements are different in ant and bee workers versus queens & kings (the reproducing adults), but this is not the case in all eusocial animals. Still, it would be worth a close look.

Check out this album on Flickr with my shots of convict fish (the cover image is a juvenile, in mid-water):

So, Where Did The Convict Escape From?

There is a very interesting paper by Wainwright and colleagues (2012) which shows by using molecular phylogeny (DNA sequence comparison) that the convict fishes are the closest relatives to the Cichlids, the popular aquarium fishes which are a substantial part of the freshwater faunae of South America and Africa. A lot of these Cichlid species have evolved very unusual and highly adaptive reproductive strategies: Discus Cichlids “suckle” their fry with nutrient-rich mucous which they secrete from their skin, almost like mammals. Other cichlids stay as breeding females in snail shells hoarded by males, and yet other cichlids breed cooperatively (groups defending nests).

A close relationship between the Cichlids, with their unusual reproductive strategies, and the convict fish, with its unusual juvenile-adult relationship is a very curious finding! Did the convict fishes branch off from the base of the Cichlid family tree, and take with them the tendency to play with reproductive and social systems?

Only one Cichlid is a true marine fish, Tilapia guineensis, even though many others can tolerate saltwater. So at least one transition between fresh and saltwater life must have taken place in the Cichlid/convict fish family tree.

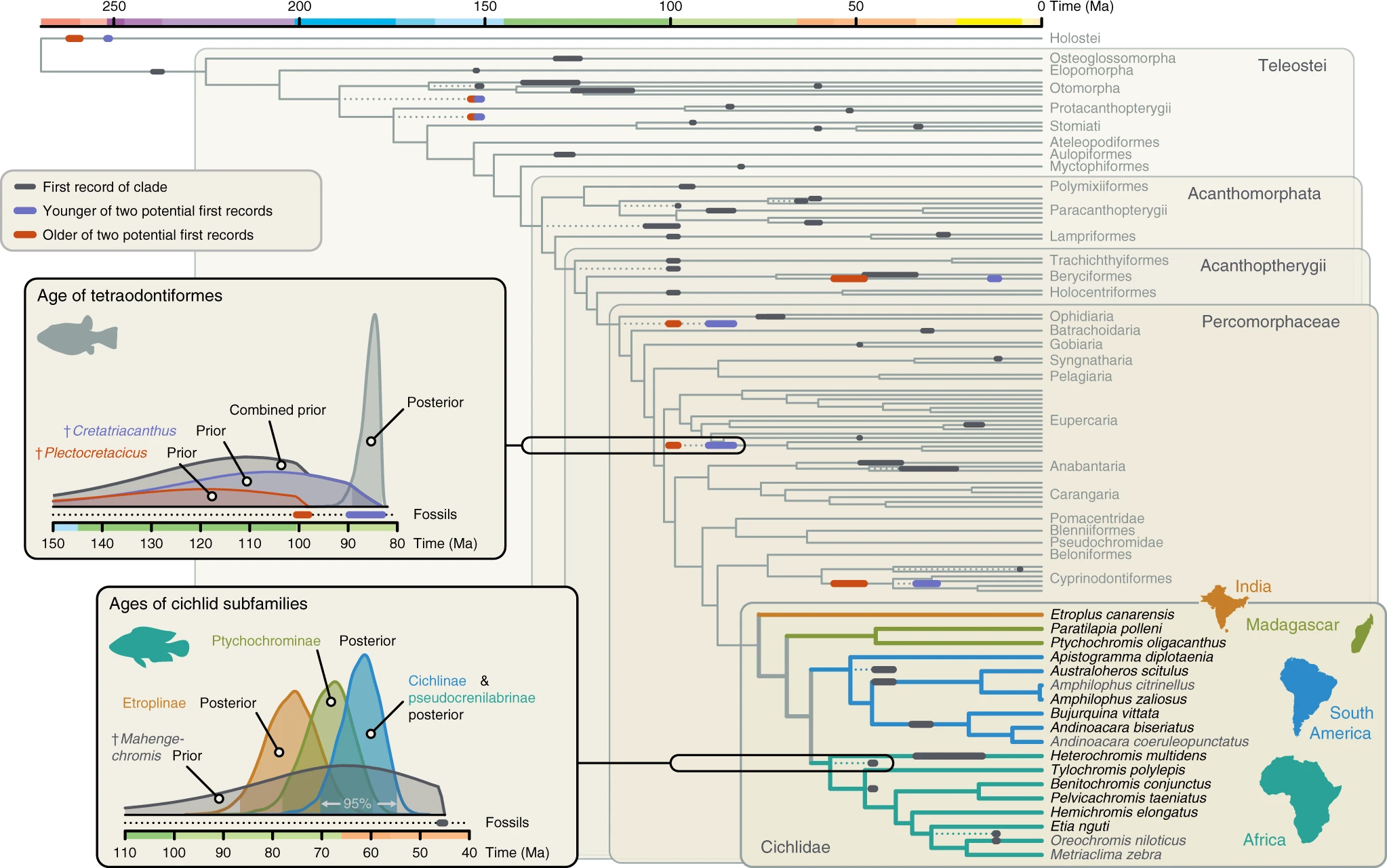

Matschiner and colleagues looked at early cichlid evolution in their very well-illustrated 2020 paper. Again, they use DNA sequence comparison to reconstruct a family tree. They find that the Cichlids evolved well after the breakup of the ancient Gondwana continent (about 75 million years ago), which contained the landmasses now making up South America, Africa, and India.

The deepest branch of the Cichlid family tree is an Indian species (orange in the family tree below) – this is where the convict fish would have branched off. India is also closest to the present-day distribution of the convict fish, and the Indian Ocean is contiguous with it. Matschiner and colleagues conclude that freshwater cichlids could have reached the different landmasses by oceanic dispersal or they could have undergone multiple transitions from marine to freshwater to colonize each landmass independently.

I hope this was interesting! I only meant to write an extended caption for a video of the convict fish which I filmed last weekend, and it turned into a rave about fish evolution. PS: Please check out my new book on gobies.

Best Fishes,

Klaus

References

Stiefel, K. M. (2013). Why are there no eusocial fishes?. Biological Theory, 7(3), 204-210.

Last but not least, here is my iNaturalist entry for the recent find:

It seems, based both on the distribution listed in Fishbase and the one seen on iNaturalist, that this fish is a true coral triangle occupant, with no spread to the adjacent tropical and subtropical regions.